December 19th. Surgery day …

The birdsong of the new day wakes me. If I had been sleeping on my good ear, I would never had heard it.

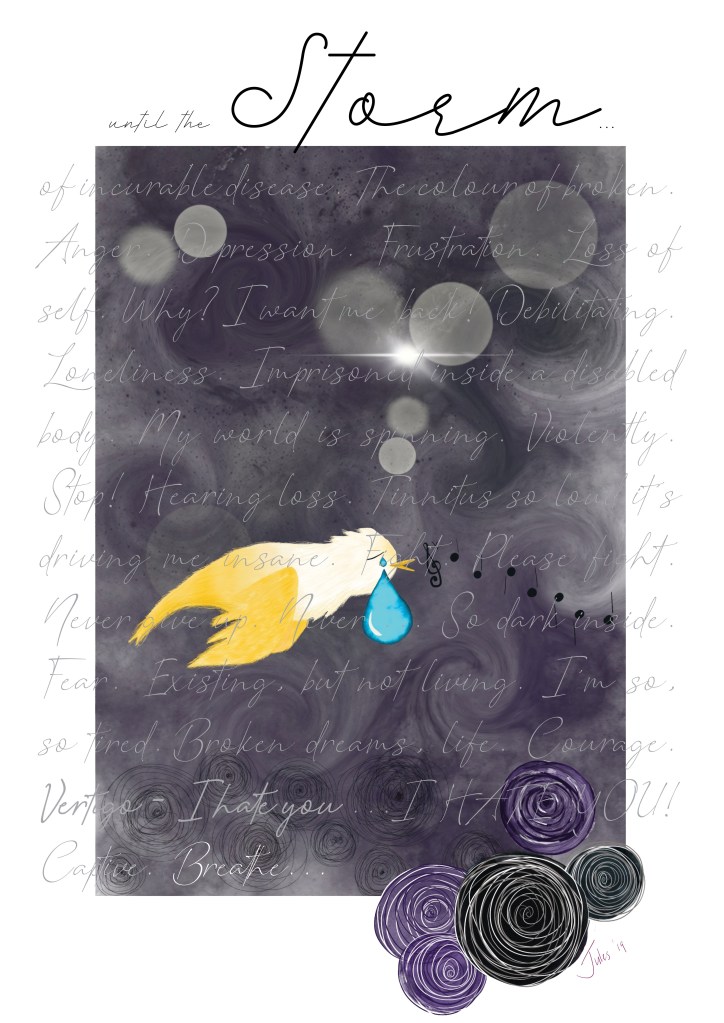

I’m thankful for that precious moment. It’s been my survival mantra since battling the ferocious Meniere’s disease. Look for the small things that make me happy, no matter how small or insignificant to others. It’s been 24 years of Meniere’s disease now. And it’s been a helluva journey that had me on my knees pleading for mercy many times as I battled the violent, abhorrent vertigo that left me a shadow of myself, lost in the darkness of depression, trying to find me, my old happy, carefree, confident, successful self. Menierians know exactly what I am talking about.

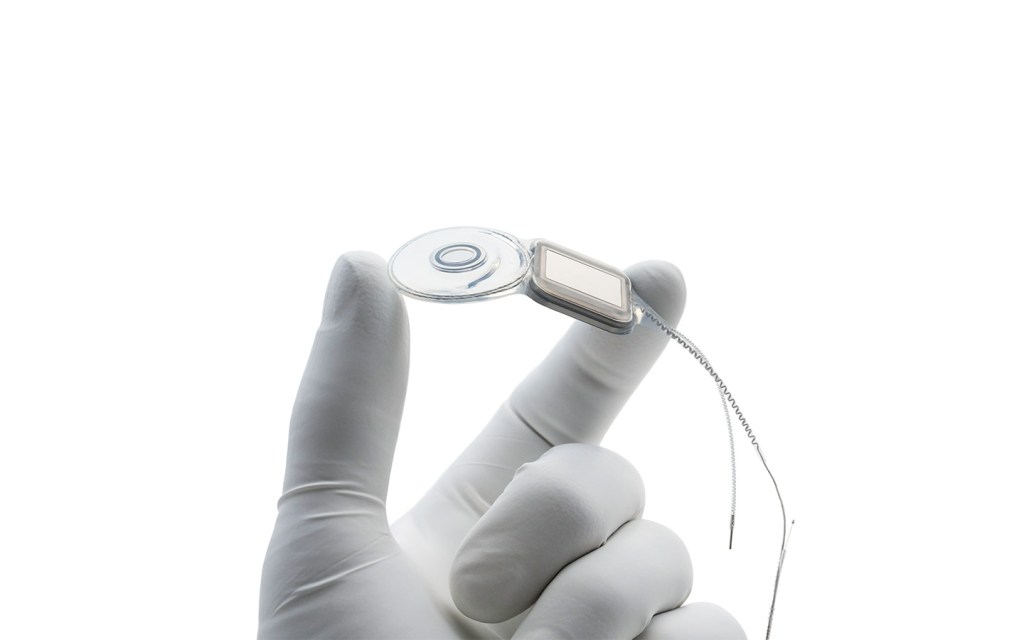

I blink away my past. Today’s the day. The surgical step in regaining my hearing, I think to myself. There’s no turning back. Yesterday was proof, more than enough, that I need the Cochlear Implant.

I climb out of bed and walk to the window and look out. There is still smoke haze hanging about from the 100s of fires that have been burning, many of them lit by people who think lighting fires is a fun thing to do. How dare they? I shake my head. We desperately need rain.

I change my focus. I need to finish breakfast by 7:30am and then fast for surgery. Mentally, I tick off what I have already done for today:

* Organised my daughter to spend the day with her father (my husband), to make sure he is okay while I am having surgery. He gets a terrible look of worry on his face, filled with sorrow, when we talk about the possibility of me having vertigo again. It breaks my heart. It’s a stark reminder that Meniere’s has a powerful impact on those who are spectators to what we go through with this horrid disease.

* Organised for my mum to catch a lift with us to the hospital.

* Organised for my two sons to pick up my dad to come and visit me after the surgery.

* Laughed at the absurdity of all the organisation I must do to ensure that the wheels turn smoothly.

Time for me.

* Breakfast before 7:30, then fasting. Toast and tea and chocolate 😊

* Pack the overnight-stay bag for hospital.

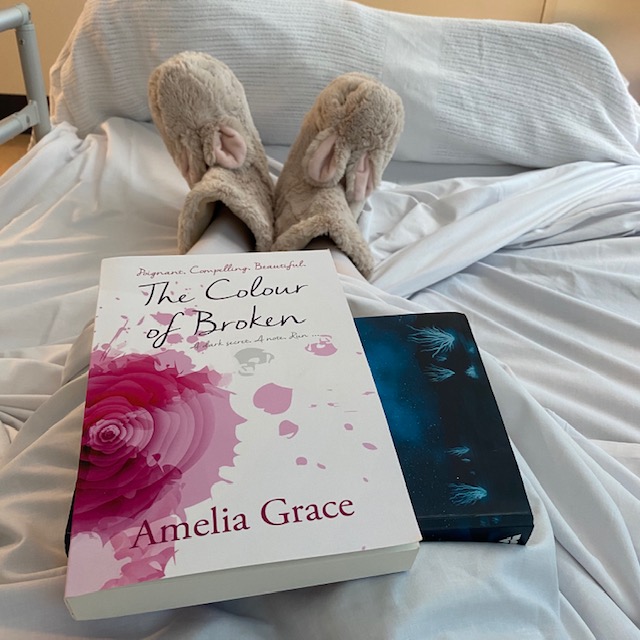

* Race to Target to buy some slippers for hospital. I have never owned any. I choose the bunny slippers because I have always wanted to have a rabbit as a pet. In Queensland, Australia, where I live, it’s a $63,000 fine if you are caught with a rabbit. This is the closest I can get.

* Double check paperwork.

I still for a moment. Vertigo. I have a terrifying fear that it would be awakened by the procedure. My shadow, Meniere’s, is dancing around me smiling. I raise an eyebrow at it and it stops.

The clock ticks over to 10am. It’s time to go. It’s time to start a new chapter in my Meniere’s journey.

I hug each of my sons and tell them that I love them. My eldest son tells me he loves me, and I hear it easily. My youngest son says something after I tell him I love him. In true Meniere’s deaf ear fashion, and one sided hearing, I can’t hear what he said and say my usual, ‘I didn’t hear you, can you say it again?’ and he says with more volume and clarity, ‘I love you, too.’ My heart melts.

I do a final swoop of the house. It is clean and tidy. Then walk to the front door.

My husband has my hospital backpack slung over his shoulder, and my daughter, her heart more beautiful than sunshine, stands beside him. They watch me, worry etched on their faces. I suck in a deep breath, controlling the deep emotion that tries to surface, not for me, but them. I don’t want them to worry.

‘I have an amazing feeling of peace. No anxiety at all,’ I tell them. And it’s the truth.

The front door closes with a feint click. It’s symbolic in a way. One door closes, another opens…

I walk to the car thinking, Anxiety, where are you? My shadow, Meniere’s, and me, are going in for surgery. Where have you gone? I can’t get over the feeling of peace that envelopes me. I decide to accept it and receive this gift from my faith, with a full and thankful heart.

Our car pulls into my parent’s house. Mum and Dad greet me with a smile. The universal language that puts you at ease.

‘Feeling nervous?’ my dad asks, making his hand shake for effect.

‘No. Not at all,’ I answer. Dad raises his eyebrows at me in disbelief.

‘I’m nervous for you,’ my mum chips in.

‘Good on you, Mum,’ I say, offering her a smile.

I hug Dad. Mum sits in the car, then me, and we are off. I’d love to listen to some music with my good ear in the car, but Mum chatters on. I’m guessing it’s her nervousness.

We arrive at the hospital and check in, then proceed to the surgery waiting lounge. Me and my family take a seat together, while my shadow, Meniere’s, bounces on the empty seats. I shake my head at it. I look for my friend, Anxiety, but he’s still not here.

It’s 11:30am. There’s quite a few adults and three children awaiting surgery, and a few of their partners and family members. I watch a man entertain his daughter with a Christmas Elf plush toy. I decide that he is more amused by what he is doing than his child. My shadow, Meniere’s, is sitting on the floor in front of him, watching.

At 12 pm, I’m called to a room by a nurse. She does the pre-op check – temperature, blood pressure, a million questions relating to my health. She tells me that my surgery is scheduled for 2pm, and I return to the waiting room.

At 1:15pm, my anaesthetist appears. I know what he looks like because I Googled his name a couple of weeks ago. My husband and I follow him to a room where we sit and wait for him to speak.

He greets me, talking loudly, over-pronouncing every word like I am totally deaf in both ears. I think of that annoyance profoundly deaf people have where normal hearing people think the person will hear better if they talk loudly.

I tell him I have one good ear and can hear him well. He smiles, and immediately his volume of voice returns to normal.

He asks me medical questions revolving around how I have reacted to anaesthetic with previous operations and takes notes, then I tell him that I have no anxiety about the surgery, and watch for his reaction, both facially and non-verbally with body movement. It still worries me that I’m so peaceful. I am an overthinker after all. I ask him if it is that a thing, like a phenomenon? Or, is there a psychological explanation for it?

He shakes his head and replies, ‘It’s good not to have anxiety.’

His last words before we exit the room are, ‘Don’t worry. I’ll look after you, I promise.’

We return to the waiting room. I keep looking at my watch, wondering when I will be called in for surgery preparation. It’s getting closer to the 2pm surgery time.

At 1:45pm, I am greeted by another nurse. It’s time to go. I hand out hugs and kisses to my husband, daughter and mother, then disappear, following the nurse to yet another room, where she asks me what my name is and my date of birth. She gives me a medical bracelet and cross checks the ID number on it with my paperwork. She shows me the change room, where I am to change into the hospital gown, including covered bare feet and a hospital robe. Once I am dressed, she places tight stockings on my lower legs to prevent blood clots during and after surgery. Then I’m led to a very comfortable recliner chair in another waiting room with a television, where she places a warm blanket over me.

And I wait. But it’s a good time for reflection. I think back to the posts from the Cochlear Implant Experiences Facebook group I joined four weeks prior. The discussions and support of other members on there and what I have learned from them has been invaluable.

It is 2:10pm, and I watch other patients come and go. I watch the television, which has closed captioning, then decide to close my eyes for a bit. I hear my name, and I follow another nurse to have a heart trace done (ECG) before returning to the waiting room. Finally, a theatre nurse calls my name, and I follow her to a hospital gurney that will take me to surgery. I don my surgery cap, hair tucked in. I listen to the nurses chatter about holidays they are taking, then my gurney is wheeled to a holding bay. The theatre nurse tells me they need to change around the operating theatre because they will be working on my left ear. She disappears.

My surgeon enters my holding bay with a smile. He approaches me on my left side, then quickly moves to my right side. ‘You will hear me better on this side,’ he says. I love him already.

‘I need to draw on you to make sure I implant the correct ear. Tell me what surgery you are having done?’ he says. It’s a question I have answered many times already, as well as my full name and date of birth. Surgery protocol.

‘I’m having a cochlear implant in my left ear,’ I answer.

He nods and smiles, then leans over and draws on the left side of my neck, just below my left ear. ‘See you soon,’ he says, and bounces out of the room with too much energy.

Five minutes later, my theatre nurse is back, and we are travelling the halls of the operating theatres. We enter the surgery room, and I gaze around, taking it all in. I see my surgeon studying my MRI, arms folded. He turns and smiles at me. The nurse lines up the gurney to the operating table, and I shuffle over to it, then lie down, ensuring that I am in the middle of the narrow table.

I am surrounded by the anaesthetist, a theatre nurse and my surgeon.

The nurse asks, ‘What is the name of your surgeon, and what is your full name and date of birth?’

As I say my surgeon’s name I look at him. He nods his head and his brown eyes show that he is smiling. I answer the rest of the question and the nurse checks my bracelet ID number to my name.

‘What procedure are you having done today?’ she asks.

‘I am having a cochlear implant in my left ear,’ I say. They all nod.

And then the movement begins. The anaesthetist straightens my right arm on positions it on a support board that juts out from the operating table, then places a tourniquet around my upper arm. He taps my lower arm a couple of times and inserts a cannular. Within 30 seconds I feel myself getting sleepy. The last words I hear are, ‘Take a deep breath,’ as the anaesthetist places the mask over my face…

I wake in recovery to the sound of my name being called. I open my eyes and become troubled by what I see. My biggest fear was waking to vertigo, and then having vertigo for days or weeks after surgery.

‘I have double vision,’ I say to the nurse, then close my eyes. This isn’t right, I think. Nowhere in my copious amounts of study and research was double vision mentioned.

I open my eyes again, and the double vision corrects itself. I feel my body relax after a small moment of panic.

The nurse checks my temperature, blood pressure, oxygen level and heart rate. I keep my eyes open, focussing on any sign of vertigo. None. I then become aware of a tight bandage around my head, over my ear. I have no pain, which, I assume is due to any pain medication given while I was unconscious.

In the next moment, my hospital gurney is moving. I’m being taken to my room for the overnight stay.

As soon as the hospital bed is in position in the room, I look up to see my husband entering, worry painting his face like a fractured mirror. I smile at him, and instantly his worry vanishes, like it has evaporated into thin air.

The nurse fusses about, conducting her observations, recording everything she needs to, and asks if I have any pain, which I don’t. My heart rate is sitting at around 58 beats per minute, but that is normal for me.

Then my mum and daughter arrive. My mum smiles slowly, while Claire eyes me warily. She has seen me with too many tears in her lifetime. I smile at them to put them at ease, but I know they are worried, as their furrowed eyebrows plead for answers to unasked questions.

‘I did it,’ I say. ‘No pain at all. I woke up with double vision. But that’s all good now.’ I touch the bandage around my head.

‘Nice head band,’ my daughter says with a smirk. I grin back at her. She has a way with humour that we both understand. My husband and three children have learned to deal with my Meniere’s monster with humour to make me laugh. It’s the only way for us all to cope as they watch me fall apart in front of their eyes. They are brave. And observant. And beautiful. This humour from my incurable disease is a bond that holds us together as they gather around me to hold me up from falling in a heap.

I look up as my two sons and my father enter the room. Well done, boys, I think, Grampy would have loved spending time with you in the car.

Amongst the chatter and explanations and assuring them that I am fine, I discover a tray full of food – chicken soup, a meat dish, vegetables and mashed potato, cake, tea, milk and two bottles of water. Yay! I’m starving! I eat happily, my family tasting this and that as well. The nurse walks in for observations and tells me the surgeon was very happy with the operation. He x-rayed the position of the placement of electrodes while I will still under the general anaesthetic, and that he will be in tomorrow morning to remove the bandages.

After my family leave, I settle in for some much-needed sleep amongst the hospital alarms and beeps.

Still no pain at the surgery site.

Friday 7am…

My surgeon enters the room with a calming presence.

‘How are you?’ he asks. His gaze is focussed on my face, waiting for my answer.

‘Great,’ I say. ‘No pain. Did you give me any pain medication during surgery or after?’

He shakes his head.

‘I’ve had no vertigo. Just double vision when I woke in recovery. Are you happy with the surgery?’

‘Very,’ he says. ‘I managed to get the electrodes all the way into your cochlear.’

My eyes widen. I remember the Cochlear Audiologist telling me that sometimes the surgeon can only get the electrodes partially into the cochlear. ‘Wow,’ I say. I can’t believe it.

He walks to the basin and washes his hands, and takes some scissors from a tray, then walks around to the right side of my bed. ‘Let’s take the bandage off and see how it looks. I’ll have to ruin your great hair style,’ he jokes. He uses the surgical scissors and cuts through the bandage and studies the incision site. ‘Looks good. Sleep sitting up for a few days and don’t wash your hair. No heavy lifting or sneezing. I’ll see you on Monday at 10:45am. Any questions?’

‘Aaah – no. Just … thank you for looking after me.’

He gives me a nod and a smile. ‘Take is easy, and I’ll see you Monday.’

10am

My husband arrives. He hands me a copy of my own novel that has a main character with Meniere’s disease. It’s a gift to the nursing staff. And a gift for those with Meniere’s disease. It will help the nursing staff understand what Meniere’s is really like – physically, socially, emotionally, psychologically. We need to find a cure! I sign it for them.

After final observations and cannula removal, I am discharged from the hospital. I am in disbelief at how good I feel. And I am soooo thankful, with a heart overflowing with gratitude – my faith, my medical specialists, the nurses, my family – it takes a village.

Life is good. The light shines more brightly when you have struggled through the darkest of dark storms.

There is always hope.

Next blog. Happy New Ear! Cochlear Implant activation …

About this blog …

My Shadow, Meniere’s, is not just about the physical aspect of a Cochlear Implant – you can research about them online. I am sharing the human side of the journey towards a Cochlear Implant – feelings, appointments, the process, apprehensions, successes, highs and lows as I step into the next chapter of my Meniere’s journey.

I am mindful of those who also have incurable diseases or are walking the path of a diagnosis that is life changing. My blog never aims to undermine the severity of anyone else’s illness, disability or journey. We all deal with life with different tolerances, attitudes and thresholds. ‘My Shadow -Meniere’s’ is my journey. It is my hope that it can help others with Meniere’s disease, or hearing loss, or simply when life has a plot twist.

I also acknowledge those before me, who have already had a Cochlear Implant. Your experiences, advice and suggestions are welcome.