Cochlear Implant Activation, 9th January

The alarm is sounding. It’s 6am. But it doesn’t wake me, my husband does. I am lying on my “good’ hearing ear, so I hear nothing. He touches me to wake me and I struggle to open my eyes. I’m tired. I’m so tired. I haven’t slept well because it’s hot and humid. The night-time low was 24 degrees Celsius.

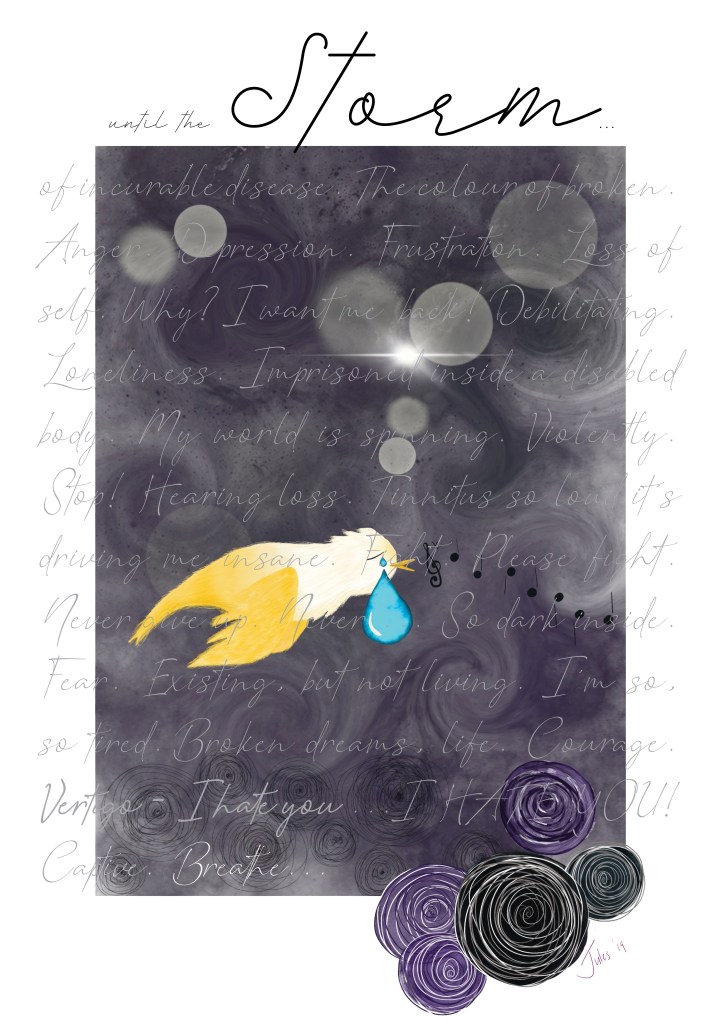

I roll over and vertigo hits me, followed by nausea.

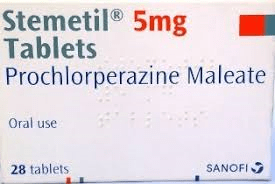

Great, I think, as my world spins. I hold still and the room stops spinning and the nausea goes. BPPV. A misalignment of the crystals in the inner ear. I know I can do the Epley Manoeuvre to stop it. But I don’t want to do it until I check with my Cochlear Surgeon in 4 weeks’ time.

I breathe a messy breath through my lips and sit up. First, I focus on the wall to check that my world is not spinning again, then stand slowly, to ascertain whether my balance feels okay. I remember it’s Cochlear activation day. But I’m so tired. Activation can’t be on a day when I am exhausted before the day begins. It didn’t happen that way in my imagination when I looked forward to hearing again. I sigh.

I push forward with my morning routine. Breakfast is low key. Toast with peanut butter and a cup of tea. Anxiety joins my shadow, Meniere’s, and me at the table. The three of us together again. I frown. Why do I feel anxious about activation, but not about the two-hour surgery where they drilled a hole in my skull three weeks ago?

I stop before the door before we leave to drive to the city. I feel safe here, behind the closed door. Comfortable. Once I open that door, my world is going to change. I take a deep breath, place my hand on the doorknob and turn it.

I step out into my future.

My husband and I arrive early for the appointment. We sit in the waiting room where the perfectly arranged magazines adorn the table, that have been painstakingly presented. When my husband takes a magazine, flips through it and plops it back on the table, I can’t help but to straighten it up so it is like the others.

I look up when I think I hear my name called.

Jane, my cochlear audiologist greets me with a smile. The universal language that puts you at ease. Anxiety, Tinnitus, Deafness, My Shadow, Meniere’s, my husband, and I follow her to her office. We all sit down, except for my shadow, Meniere’s. He’s jumping up at the window overlooking the city, and sliding down with a giggle. I shake my head at him.

‘Welcome back,’ Jane says. ‘How did the surgery go?’

‘Good,’ I say. ‘I’ve had no pain, no major vertigo, just little spins when I roll over. BPPV. I can fix that with the Epley Manoeuvre, but I want to wait until I see my surgeon in a few weeks.’

Jane shakes her head. ‘The little spins may not be BPPV. Sometimes drilling the hole in your skull can upset your inner ear and cause that. It will get better.’

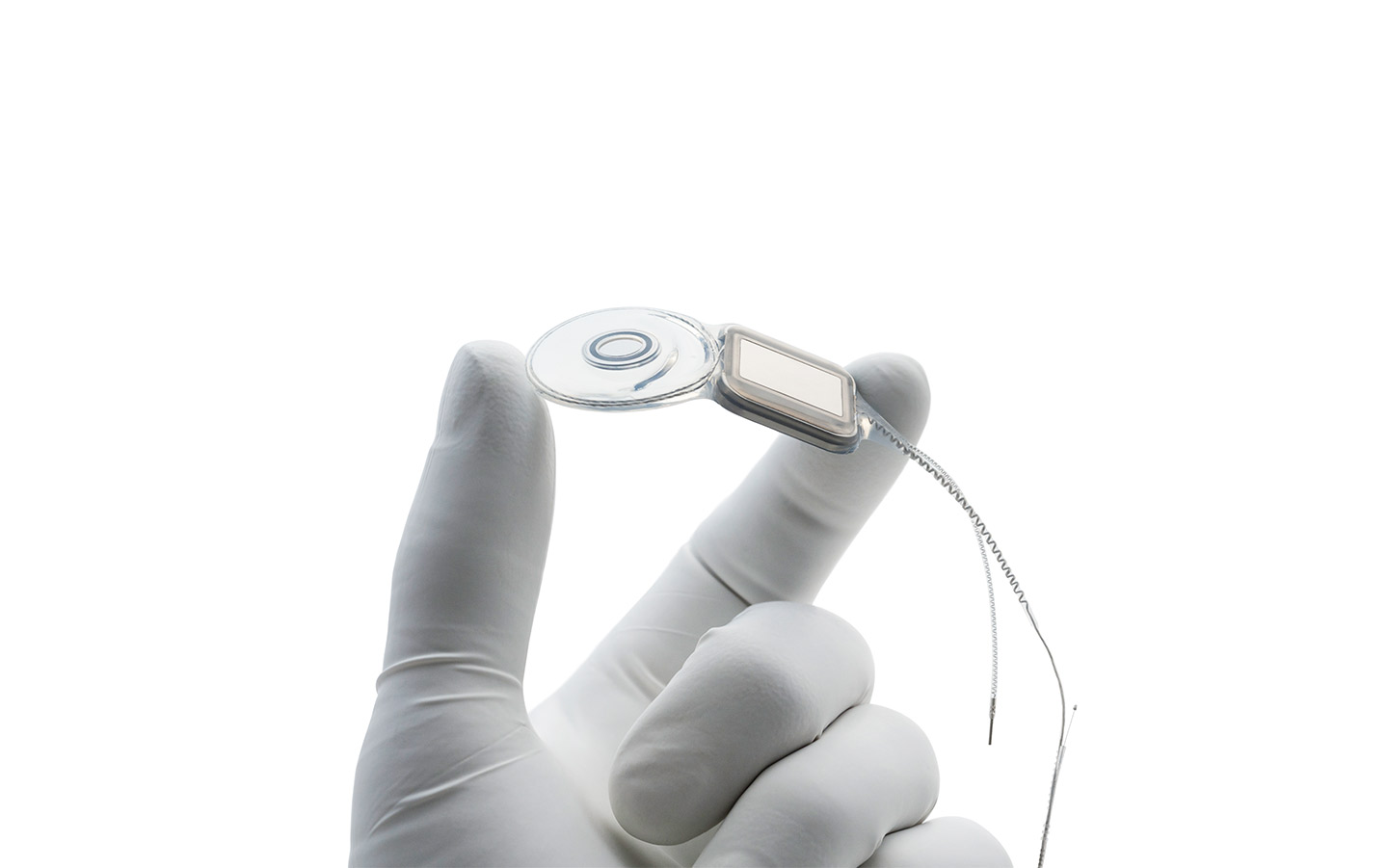

Oh. I am surprised by that information. I smile. ‘The surgeon managed to get the 22 electrodes all the way in. He was really happy with that.’

‘Wonderful. Plus you have two earth electrodes in there as well.’ Immediately my mind turns to the memory of me out in the storm the other day. I had rushed inside in case my implant attracted lightning.

Then, on researching lightning and Cochlear Implants, I am no more likely to be struck by lightning than anyone else. Phew!

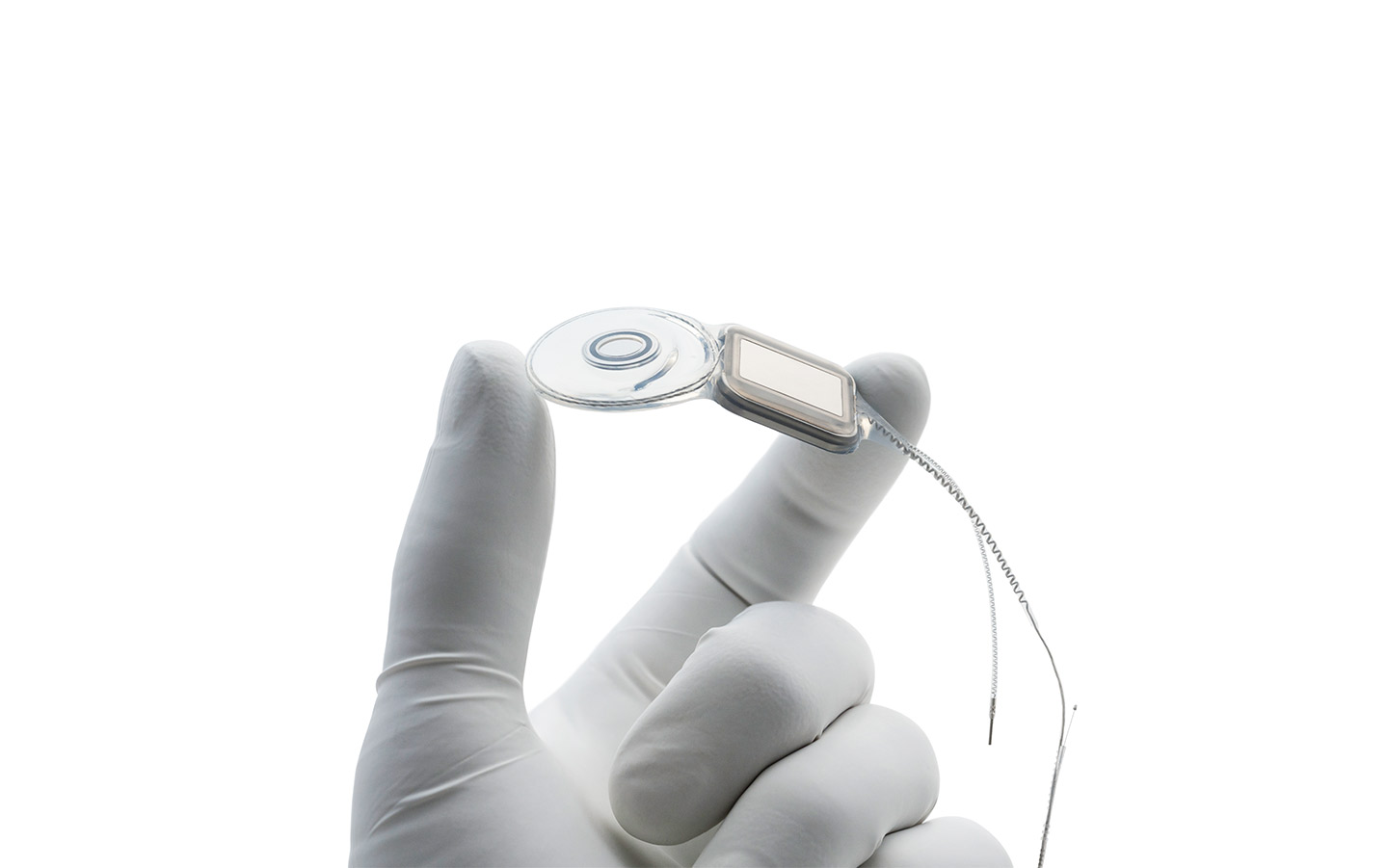

Jane turns to my husband and shows him what has been implanted into the cochlear of my inner ear. ‘The electrodes are 1/5 of the width of a hair strand, in size.’ My husband’s jaw drops to the floor. He shakes his head. It’s hard to comprehend.

‘Okay. Are you ready for today?’ she asks.

I nod, and see Anxiety double his size beside me. I want to grab a pen and stabbed him so he farts all the air out of him. My shadow, Meniere’s, sits in the corner and lowers his head. Tinnitus is doing pirouettes in a tutu. My life really is a circus!

Jane places the external hardware over my ear, attaches the transmitting coil to the magnet that sits under my skin on my scalp, all the while explaining how it works. The enthusiasm in her voice tells me how much she loves her job. She is super excited about switching on my Cochlear Implant.

Once the processor and transmitter are in place, Jane sits on her chair. I’m knotting my fingers together as my skin burns. I frown. I can’t hear a thing in my Meniere’s ear. Nothing has changed. My tinnitus is still screaming at me.

She attaches a wire to the speech processor around my ear and taps a few keys on the computer. She smiles and says all the electrodes are looking good. Then she taps another key and I still. My heart starts to race and my eyes widen. I can hear a few crackles and pops.

‘Can you hear this, Julieann?’ she asks in her English accented voice.

Three beeps sound in my deaf ear. Then another three at a different pitch, and another three.

‘Yes,’ I say, my voice cracking. I cover my eyes as tears fall. I can’t stop from crying.

‘I can hear that,’ I add.

‘Good,’ she says and smiles. ‘Are you okay? There’s tissues behind you.’

‘Yes,’ I squeak. I grab a tissue and look over at my husband. His eyes are red-rimmed and wet. He has been a part of my journey. Twenty-five years of being a spectator to my incurable Meniere’s disease, where he could do absolutely nothing to help me, except clean out the vomit bucket time after time after time after I had vomited violently whilst spinning, or attending the emergency room when I was so dehydrated from vomiting that it was dangerous to my health, or when we thought the violent spinning wouldn’t end. We’ve been married for 31 years. He knows exactly what physical, emotional and psychological toll it has taken on me. He has seen me during my darkest days.

Yet, I spared him from witnessing the darkest of dark days when I no longer wanted to be here, when I wasn’t the colour of grey with an “e”, nor the colour of gray with an “a”, but the colour of black.

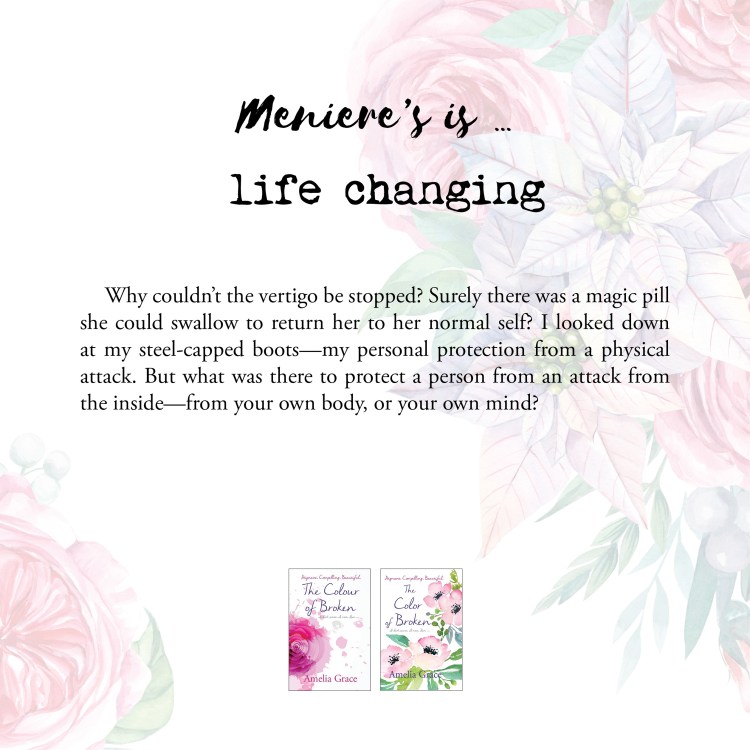

From my novel – ‘The Colour of Broken’ – Yolande, the main character is sitting in the chair, talking to her psychologist …

‘What colour are you?’

I took a deep breath and twisted my fingers together. My stomach tightened. I cleared my throat. ‘The colour of broken …’

Dr Jones was silent.

I stopped breathing when anxiety rose inside me like a wall of lava, about to incinerate me. It was freaking me out that she now knew this about me, and that she had not reacted to the description of my colour.

‘And what colour would that be?’ she finally asked.

I breathed out through my lips, slowly, steadily, counting to five in my head. ‘Gray with an “a”.’

‘There’s a difference?’

‘Oh, yes. Grey with an “e” is very different to gray with an “a”.’

‘How?’

‘Grey with an “e” is like the rain clouds. It’s melancholy, but an enjoyable melancholy that builds up until it releases, and then it’s like petrichor, the smell of the rain after warm, dry weather. Satisfying. Grey with an “e” is also when deep thought, philosophy and ponderings happen. Everyone should experience grey with an “e”, it helps to discover parts of you that you never knew existed, and it can vanish without leaving a bitter aftertaste.’

‘Tell me about gray with an “a”.’

I looked down at my knotted hands. ‘Gray with an “a” is … never enjoyable—it’s a very dark gray. It’s self-judgement, doom and gloom, forever hanging around and within. It wants to drag you into the dark abyss of the colour black, that absorbs all colours … the colour of self-condemnation, the colour of depression, the colour of death of the physical body.’

‘But not the spiritual body?’

‘No.’ I didn’t want to add any more to this conversation. It was painful to talk about.

‘So, me being a supposedly normal person, could I see your gray with an “a”?’

‘No. Because I mask it. And my gray with an “a” is not a plain gray with an “a”. It’s a crackled dark gray, with other colours that seep out … sometimes.’

‘What colours would they be?’

‘Drips of red for anger … specks of black—’ for self-hate, ‘—for my secret, blushes of pink for my love for Mia and my family, and explosions of turquoise that screams at me to love myself …’

‘That’s very insightful, Yolande. It’s highly intuitive. I’m curious … when you look at me, what colour am I?’

I hesitated before I spoke. I never told anyone the colour I had appointed to them for fear of them running from me. But Dr Jones, she was different, she would understand …

‘You are … magenta,’ I finally said. ‘It’s the colour of a person who helps to construct harmony and balance in life, hope and aspiration for a better world—mentally and emotionally,’ I said, and held my breath, waiting for her reaction.

She raised her eyebrows at me. ‘That’s an amazing gift to have in your mind toolbox, Yolande. Does it ever lie to you?’

Jane says, ‘I’m going to switch on each of the electrodes, one by one. Tap on the table when you hear the beeps.’

And so it begins. As I hear beeps, and tap on the table, hope rises in me like a flower blooming, facing its sun. I hear 21 out of 22 electrodes. Jane is ecstatic.

I am in shock and a tears trickles down my face. I can hear!

She looks at me and smiles. ‘Do you need a break?’

‘No,’ I say. I am beyond fascinated. In awe. What an age to live in with medical science, discoveries and inventions.

‘Let’s try some speech,’ she says. She taps a few more keys, and suddenly there are words in my Cochlear Implanted ear.

I start crying, wiping a thousand tears from my cheeks. ‘I can hear what you are saying,’ I sob. ‘But you sound like you have been inhaling helium!’

Jane’s face lights up with a smile. ‘You can! That is so wonderful!’ She is looking at me with a contagious joy.

She continues talking. I hear her chipmunk voice, but I can’t understand her. She keeps talking, and with my good ear, I understand that, as she keeps talking for another 10 minutes, my brain will start understanding better. She says the hearing part of the left side of my brain has been used for some other processes since I lost my hearing. And now it is shuffling, trying to find my speech and sound memories, to make sense of what it is hearing. It is using auditory pathways and memories, and must work at a higher level to pull together the information to have bi-normal hearing. The brain must code all the information coming in.

And then suddenly, like a light has been turned on, I can understand much of what she is saying, as words. Not all of them, but quite a few. For the words I don’t get, my mind fills in the blanks with words to match the meaning of what she is saying.

I am speechless.

She turns to my husband. ‘Say something to Julieann.’

I look at him and smile.

He smiles back. I see his lips move. I wait for the sound of his chipmunk voice. I swallow and my skin burns. His voice doesn’t even register as a chipmunk. I can’t hear his voice at all!

His eyes widen in panic.

Jane jumps in quickly in a calm and encouraging voice. ‘That’s okay. It will happen.’

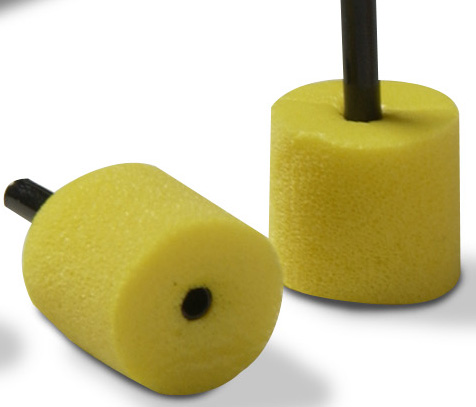

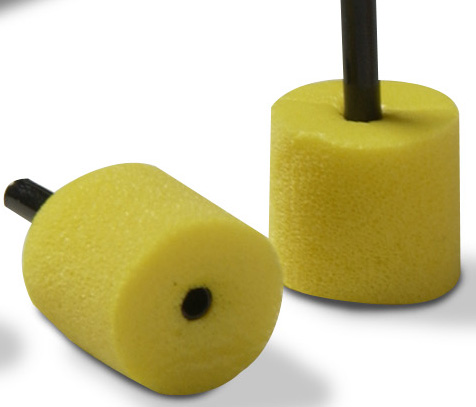

Jane reaches over and pulls out a foam ear plug and puts it firmly into my good ear.

Then she places a hearing muff over my good ear.

I have lost all hearing that I have been relying on to hear and understand conversation.

Jane continues talking like we are in a normal everyday conversation. I stare at her, trying to get what she is saying. It is so hard. Her voice is sound, but not words.

I focus harder, and slowly some of the sounds become words.

She stops and asks me a question. I stare at her blankly. I am trying to figure out what she has asked. I am trying to piece together what words I understood of the question, and with the missing words, I am working on using any visual cues from what she is doing, plus I am trying to read her lips.

Finally, I answer with a smile. ‘Yes. I can hear you. And your speech is starting to sound like words.’

‘Well done!’ she says. And I understand her chipmunk voice perfectly. She then explains about the delay happening in my brain with the speech and understanding. She knows how hard I am working to try and understand the new input into my brain.

‘Can you hear this?’ she rattles a piece of paper in front of her.

‘Yes,’ I say, although it doesn’t sound like paper, but an unrecognisable noise.

She stands and goes behind me and I hear another noise. I nod my head. I can hear it. She shows me a tissue that she rubbed in her palms. I am absolutely gobsmacked. She asks me to repeat words. I get most of them right, guessing some of them. Then Jane covers her mouth so I can’t read her lips. I hear her, but not clearly enough and get some of the words wrong.

She turns to my husband and asks him to speak to me again, and he does.

I still can’t understand him, at all.

She tells him to slow down and breaks his sentences into chunks, and not to run the words together.

He tries again.

I smile at him and say, ‘No. You don’t sound like Darth Vader.’ He smiles. He’s happy now.

Jane grins. She goes through the Cochlear Australia backpack that is mine to keep. It is filled with bits and pieces for care of my Cochlear Implant external hardware, plus other bits and pieces and chargers and batteries and paraphernalia. She shows me how to use everything, and then asks me to do the same. It fits in perfectly with my teaching philosophy.

After two hours of intense concentration, she asks in her chipmunk voice, ‘Is there anything you want to ask me before you leave today?’

I think for a moment. I’ve had way too much information overload. My brain is working double time and I am tired. ‘Is it okay to wear my new hearing to the Big Bash Cricket tonight?’

Jane laughs. ‘Yes. If you like. It will be very noisy though.’

My husband and I leave her office, take the elevator and walk out into the real world. I stop for a moment, wondering if I can hold my emotions together. The impact of activation has been overwhelming. Two hours ago I had walked into Jane’s office deaf in one ear. Now I walk out, hearing with two ears.

The thought is profound.

My husband looks at me. ‘Are you okay?’ His eyebrows are pulled together. For a moment, I wonder how hard this has been on him?

‘Yes.’ I blink away tears, then start to walk again.

The world is noisy. Terribly noisy. I hear everything in a tinny, echoing, chipmunk way. My brain is detecting two lots of hearing with everything – my deaf, now hearing Meniere’s ear, hearing conversations of chipmunk voices, and chipmunk city noises of its own while I listen with my good ear to the same thing with normal hearing. The two sides of my brain haven’t synced yet. They are acting independently of each other.

I laugh to myself. How privileged am I to be able to experience this oddity? My heart overflows with gratitude.

I take confident steps into my new normal. Into my future. Bilateral hearing. Something I haven’t had for 15 years. Something I thought would be impossible.

Before I go to bed, I remove the external hardware. Immediately my ear feels full and profoundly deaf. My tinnitus returns. But that’s okay. That’s my other normal. Two of me.

I reflect on my most extraordinary day – five times I have stilled at big moments:

- When the Cochlear Implant was activated and I could hear! My mind was blown!

- When I heard music. I cried so hard my husband wanted to pull over the car to make sure I was okay.

- I located the direction of a sound. I haven’t been able to find where a sound is coming from for 15 years. This ramifications of this for me in the classroom will change my stress level as I teach.

- I heard a man’s lower chipmunk voice while waiting to catch the bus after the cricket …

The cricket … I think back to the Big Bash Cricket and smile. On entry, I was pulled aside for a security check, the metal detector waved over and around me – it always happens to me at airports too. It’s become a running joke with my family. I held my breath, wondering whether my Cochlear Implant would set the detector off, but it didn’t.

And Jane was right. The Big Bash was very noisy. But it was so worth it. And I’m taking marshmallows to toast in the flame next time!

And number 5 … I entered our walk-in wardrobe. As I stood there trying to decide what to wear to the cricket, I froze. Something was wrong. Very wrong. My heart raced and I started to panic. I couldn’t hear anything. Not even from my “good” ear. I felt for the Cochlear Implant external hardware. It was still there. I ran my hands over my arms to make sure I was still me, and I wasn’t dying – seriously!

Something wasn’t right.

I could hear absolutely nothing. Nothing! I spoke to check that the Cochlear Implant was still working. Maybe the power pack had gone flat? I heard my own voice as well as my chipmunk voice. Two of me. I stopped and listened again in the stillness of my walk-in wardrobe.

There was silence. Utter. Beautiful. Silence. No tinnitus. After a quarter of a century. I closed my eyes and let my tears fall, covered my mouth and ugly cried.

The gift of hearing. I am so beyond thankful. I have no words to explain what it feels like to have the Cochlear Implant activated and to hear again. My faith. Health professionals. Family. Support of friends and Facebook groups. It takes a tribe.

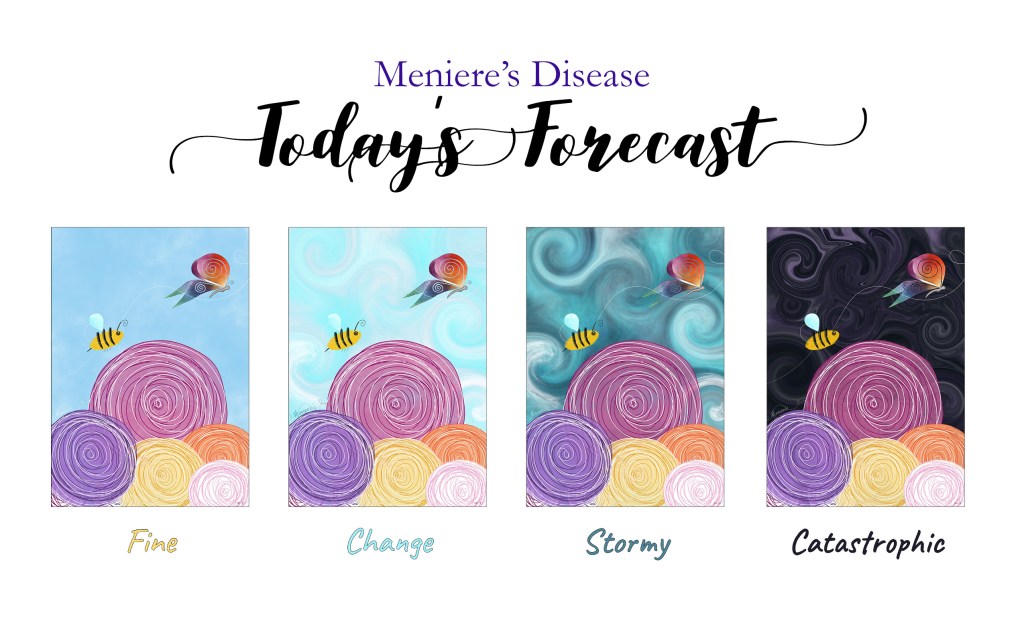

The Cochlear Implant has changed my life. On activation. It has made the impossible, possible. Meniere’s disease may not be curable, yet, but we can take back from Meniere’s what is has taken from us.

Next blog – learning to hear again …

Julieann Wallace is a best-selling author, artist and teacher. She is continually inspired by the gift of imagination, the power of words and the creative arts. She is a self-confessed tea ninja, Cadbury chocoholic, and has a passion for music and art. She raises money to help find a cure for Meniere’s disease, and tries not to scare her cat, Claude Monet, with her terrible cello playing.

https://www.facebook.com/julieannwallace.author/

https://www.julieannwallaceauthor.com/

Meniere’s Journals are available for pre-order at Lilly Pilly Publishing & Amazon (30 Jan. 2020). Profits are donated from ‘The Colour of Broken’ and the Journals to Meniere’s research to help find a cure.

About this blog …

My Shadow, Meniere’s, is not just about the physical aspect of a Cochlear Implant – you can research about them online. I am sharing the human side of the journey towards a Cochlear Implant – feelings, appointments, the process, apprehensions, successes, highs and lows as I step into the next chapter of my Meniere’s journey.

I am mindful of those who also have incurable diseases or are walking the path of a diagnosis that is life changing. My blog never aims to undermine the severity of anyone else’s illness, disability or journey. We all deal with life with different tolerances, attitudes and thresholds. ‘My Shadow -Meniere’s’ is my journey. It is my hope that it can help others with Meniere’s disease, or hearing loss, or simply when life has a plot twist.

I also acknowledge those before me, who have already had a Cochlear Implant. Your experiences, advice and suggestions are welcome.