Turn Off the Vertigo!

It’s early in the morning and I’m buzzing with excess energy. I’m restless, and failing at trying to focus on getting ready to go to work to teach secondary students. My thoughts are all over the place and I’m filled with an ocean of hope for the future of Meniere’s disease. It’s also the day after I flew to Sydney to attend the Macquarie University for a tour of the School of Engineering and Hearing Hub. Yes, I wagged school to fly interstate. It’s for a Cochlear appointment, I told my employer, leaving out the fact that the appointment was a 1hr 35min flight to Sydney.

Yesterday, I was up at 4:30am to start my day. After the flight to Sydney I caught three trains to Macquarie University Station. Anne said she would meet us here. I looked around. No Anne. Maybe she meant not right here, but at the entrance of the station. I looked up at the exit. Two massive escalators, around 100 steps each. How far underground were we?

I reached the top of the stations and stepped out into the daylight and looked up. It was such a beautiful day in Sydney.

‘Julieann?’

I shifted my gaze, expecting to see Anne. But it wasn’t her. ‘Yes,’ I said, assuming it was one of the thirteen Meniere’s people who were gathering at the Macquarie University today.

‘I’m Eleanor*. I recognise you from the Zoom sessions.’

I smiled then remembered I was a Meniere’s guest speaker at one of Sydney Meniere’s Group Zoom sessions. Technology connects us globally. ‘Hi, Eleanor.’

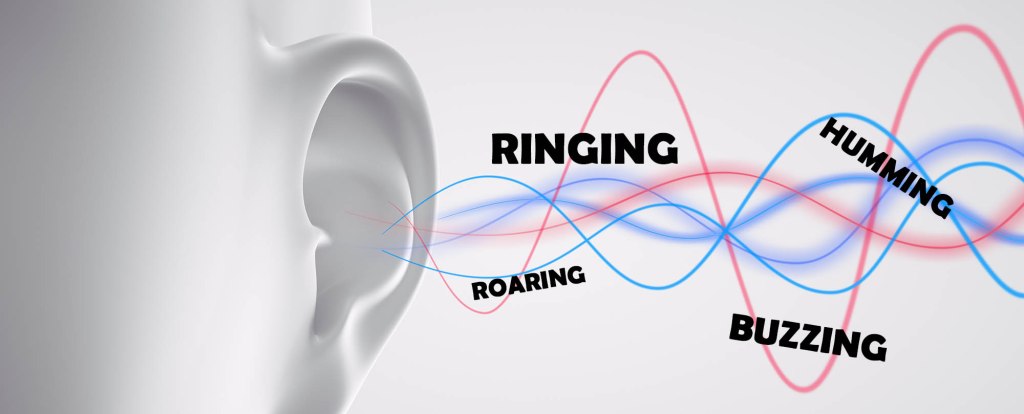

And then our conversation started. Eleanor told me her Meniere’s story and I asked her questions. At once her Meniere’s traits appeared, those traits that people with Meniere’s know so well. That turn of the head to the better hearing ear. The ‘Can you say that again?’ request. The stop in the conversation when the traffic noise became too loud. What a terrible place to share stories. I watched once again as she turned her good ear toward me to hear what I was saying. My heart cracked. That was me once, trying to listen, trying to lip read, trying to fill in the missing or misheard words to make sense of what was being said. The nodding and smiling when I should have been answering a question. Eleanor needs a Cochlear Implant. Like me. It would make her life so much easier. Dear, dear Eleanor. I wanted to hug her so tightly that all her broken bits from Meniere’s would be pushed back together. Her life story … I took a deep breath, what a strong woman she is. I was in awe of her.

And then another person arrived. ‘Julieann,’ she said. ‘I’m Amy*.’ She knew my name before I could say anything. She told me her Meniere’s story. It was her neck that was out, and once she had it worked on, she hadn’t had vertigo since, but she still has the other symptoms.

Then Anne appeared. The shaker and mover, Dizzy Anne. The Anne who started the Sydney Meniere’s Support Group . Anne who organises regular Zoom meetings with guest speakers to educate, support and help people with Meniere’s disease: Meniere’s Support Group – Dizzy Anne – YouTube. Legendary Anne with a heart of gold.

More people appeared as if from nowhere. A head count. Two people were missing. They couldn’t make it. We all understood perfectly. That horrid beast of Meniere’s disease. You can make plans, but it is the Meniere’s Monster that destroys them for you. My heart sank for them and I started to slip into that dark, dark place of long ago when that was me. When Meniere’s had taken so much away from my life and I was on my hands and knees trying to find the missing pieces of me. I lifted my face to the sunshine, thankful for my Meniere’s journey, thankful that I was able to be a voice for sufferers, and thankful that I was here today to meet the researchers working to find a cure for us. It must be coming soon. Hope.

After finding our bearings we were on the move, headed toward the Macquarie University Hearing Hub Café where our day of insight would begin.

10:30 – 11:00

We entered the café I looked for our people. Our Meniere’s researchers. They belonged to us. A noble type of HumanKIND filled with a passion to help others, or perhaps because they loved the academic challenge to find missing pieces to solve medical problems, maybe a mix of both. What is their story? What is their motivation? These were the bravest of brave researchers, tackling a terribly difficult disease to find solutions for, with the ultimate goal of finding a cure. They are my Meniere’s Superheroes.

They stood together with an easy confidence. Smiling. Their Clark Kent personas hid their superhero status. In my curious and imaginative mind I gave them each a superhero cape. Then I joined the line to order a chai latte.

I turned to see who was behind me. ‘Julieann. I recognise you from our Meniere’s Facebook group. I’m Mark*.’

I smiled. ‘Hi, Mark. How are you?’ And then we fell into an easy conversation. He told me he had a small spin while driving to the university. He shared his Meniere’s story with me. I understood completely. He also told me how he had lost his hearing in his right ear when he was young, most probably due to the measles. I knew he needed a Cochlear Implant. It would change his life.

I discovered how at ease I was in the group of Menierian’s. I’ve only met two very small groups of people with Meniere’s twice in my 26 years of this awful disease. We all suffered the same symptoms. We had been through the same journey. We were friends, instantly. No judgement. Only sincere compassion and empathy…

The Meniere’s researchers approached us and mingled while we sipped on our barista made tea, coffees, chai lattes, cappuccinos and hot chocolates, gifted to us, all paid for like we were the superheroes, and they were visiting us. I was taken back by their kindness.

11:00 – 11:30am

We walked to the Lecture Theatre on Level 1. The door opened to the impressive lecture room. I gazed up at the pitched floor with rows and rows of seats. It took me back to my own university days, and indeed of a teaching room at the school where I taught. I eased myself into the seat with a quiet confidence, keen to hear about their research.

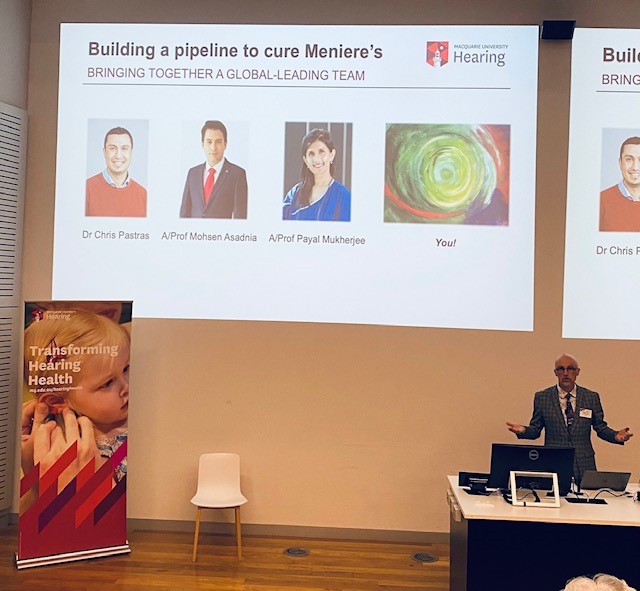

Professor David McAlpine, Academic Director of Macquarie University Hearing at the Macquarie University Australian Hearing Hub, awardee of the prestigious Einstein Fellowship, welcomed us to the Macquarie University and walked us through our program today.

Then he introduced us to the Meniere’s research team, who are building a pipeline to cure Meniere’s, bringing together a global-leading team: Dr Chris Pastras (Director of Meniere’s Disease Research), Associate Professor Mohsen Asadnia, Associate Professor Payal Mukherjee ENT (who was unable to attend today), and then he added … you.

He spoke of the importance of listening to people with Meniere’s disease. They want to help us, and they can’t do it without our involvement. Future tours and information sharing will continue with open invitations, as today’s was.

I sat there in awe as he drew us into his world of research, our world of Meniere’s. My memory cells are bursting with Meniere’s information, soaking in every single word, enraptured by the Professors McAlpine’s passion for research and trying to cure, or at the very least, find solutions to symptoms so Meniere’s people can live a quality life again.

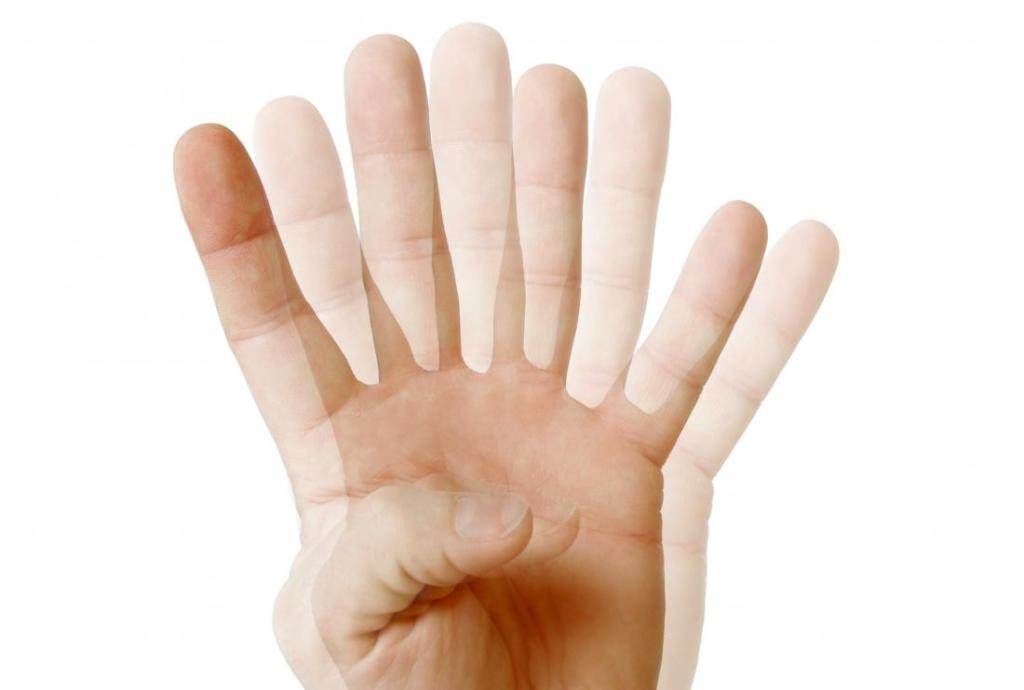

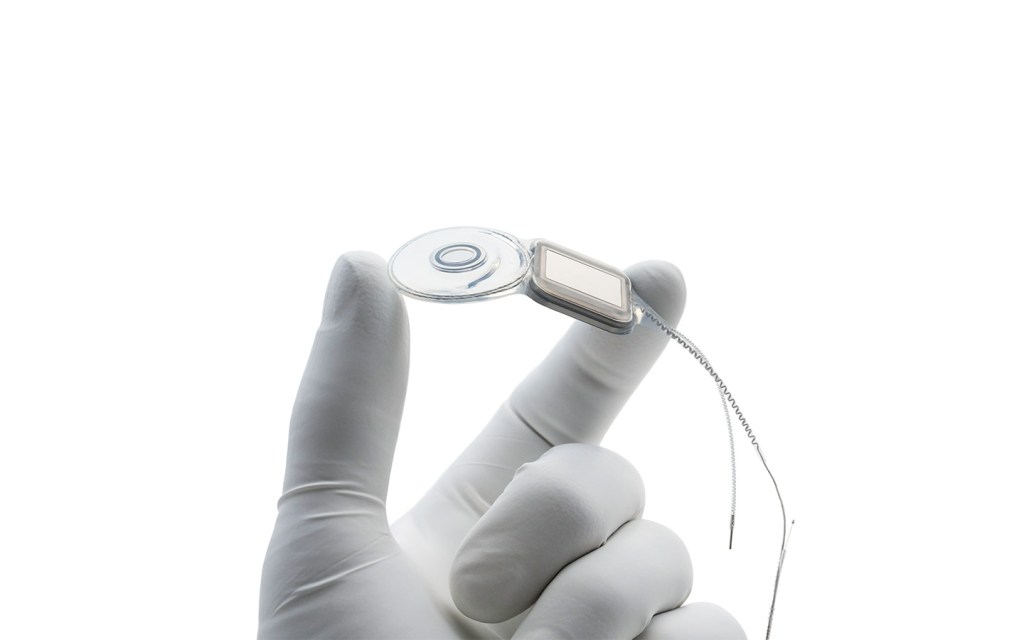

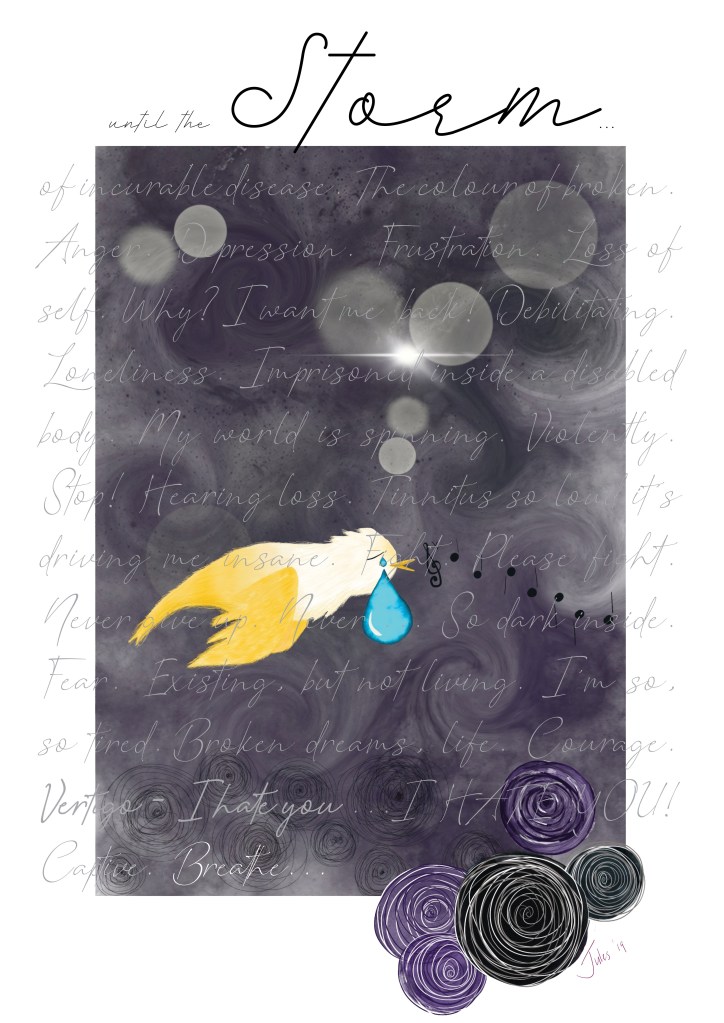

And then came the words that had me in a spin. He told us about an implantable device that will allow us to turn off the vertigo and restore our balance. I couldn’t stop myself from mouthing “WOW!” I held my breath and shifted in my seat as my eyes pooled with tears. Then I inhaled deeply to calm myself. This … is what we have been waiting for: to be able to control our vertigo without the destructive intervention, without sac decompression, without the use of gentamicin, without having a vestibular nerve section, but to just have an implantable device that acts like a switch to turn off the vertigo … mind officially blown. An answered prayer. This is a life changer. This is a life giver. This means finding our self again, the one before the physical, social, emotional and psychological broken pieces of us, after Meniere’ Disease entered our lives uninvited, shattering our sense of self – who we were, our self-worth, taking our happiness, our confidence, our friends, our social lives, our enjoyment of being able to eat whatever we wanted, our ability to take part in any physical activity offered to us.

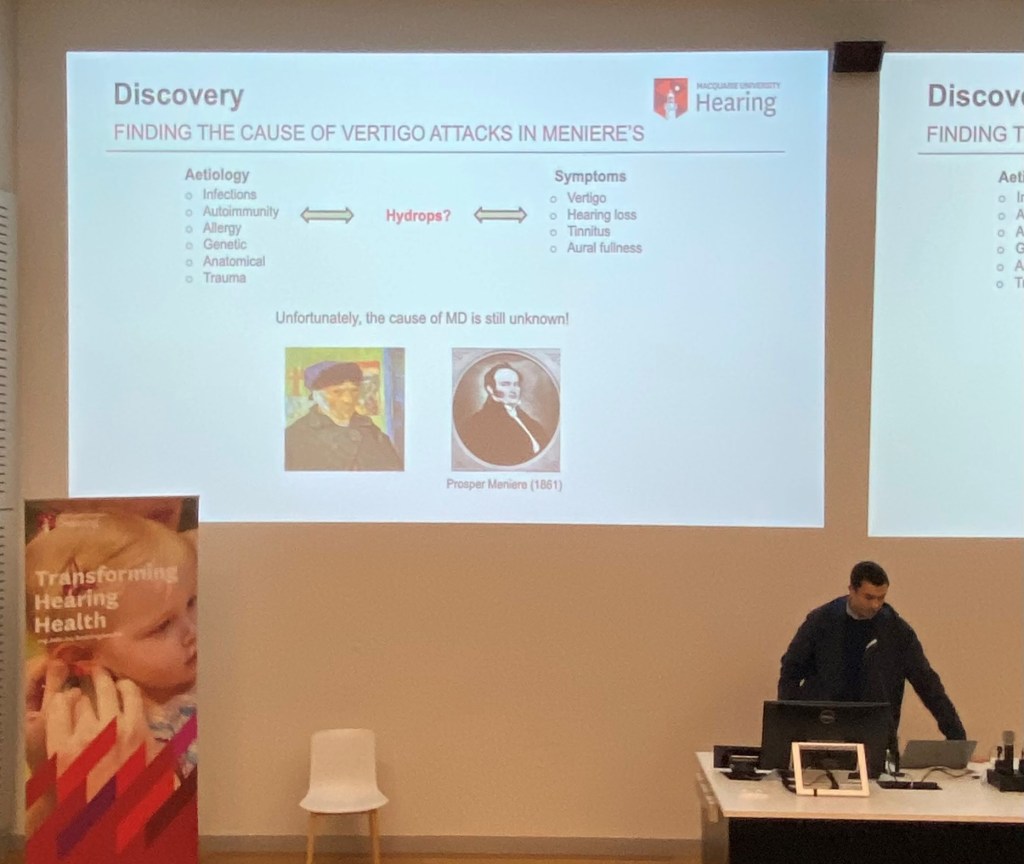

Dr Chris Pastras presented next.

Discovery:

FIND THE CAUSE OF VERTIGO ATTACKS IN MENIERE’S

aetiology <-> hydrops? <-> symptoms

Discovery:

FINDING THE CAUSE OF VERTIGO ATTACKS IN MENIERE’S

• Clinical Indicators

• Origin of Dysfunction

• Pathophysiology

Discovery:

A HOLISTIC PATHWAY FROM DISCOVERY TO TRANSLATION:

- Uncover the link between endolymphatic hydrops and MD.

- Characterise the cause of vertigo attacks for future treatments.

- Develop novel therapeutic strategies in animal models.

- Develop novel diagnostic tools for clinics.

- Improve current diagnostic and treatment strategies.

- A vestibular implant for balance rehabilitation after surgery

Professor Mohsen Asadnia followed Dr Chris Pastras.

Innovation:

ENGINEERING NOVEL MICRO/NANO DEVICES:

- Develop devices to monitor potassium and formation of endolymph hydrops which would warn the patient of an impending MD attack, allow activation of smart drug delivery systems and help to understand the progress and severity of the disease

- Artificial endolymphatic sac to replenish and ionically modulate endolymph.

Innovation:

ENGINEERING NOVEL MICRONANO DEVICES

- Development of highly sensitive potassium sensor

- Inner ear fluid – make an implantable sensor to change the ion concentrate – potassium

- Make an artificial sac to eliminate Meniere’s – has been tested and published.

- They have made a membrane that only lets potassium pass through.

Professor David McAlpine thanked our presenters and we applauded. His passion for everything that had been spoken about today and about Macquarie University and their cutting edge science applied to Meniere’s was eagerly absorbed by me, and my imaginary bucket I brought along to fill with hope from today was already full. Wagging school for the day was totally worth the guilt of missing class with my students, but also knowing that they were in good hands with another teacher who would follow the plans I had left them.

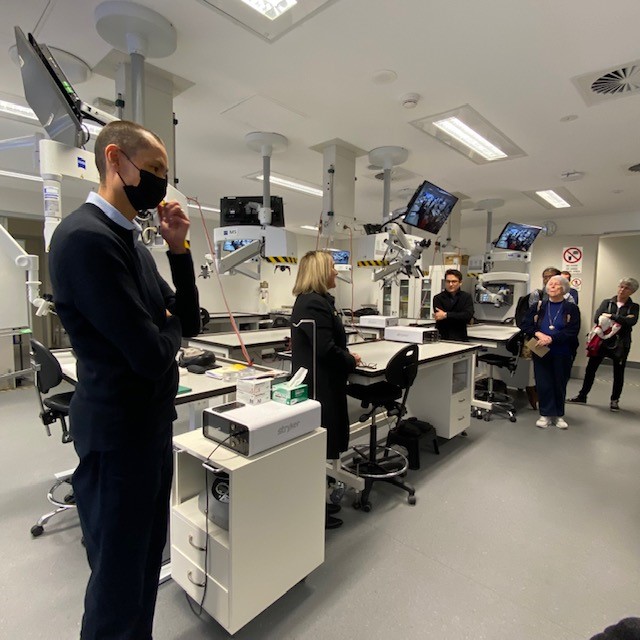

11:30 AM-12:30 PM- Australian Hearing Hub’s lab visit

We left the lecture room and followed Professor David to our next stop on the tour. It was the Australian Hearing Hub Lab. The door opened and we entered the lab room of Cochlear Implant innovation and ground breaking research.

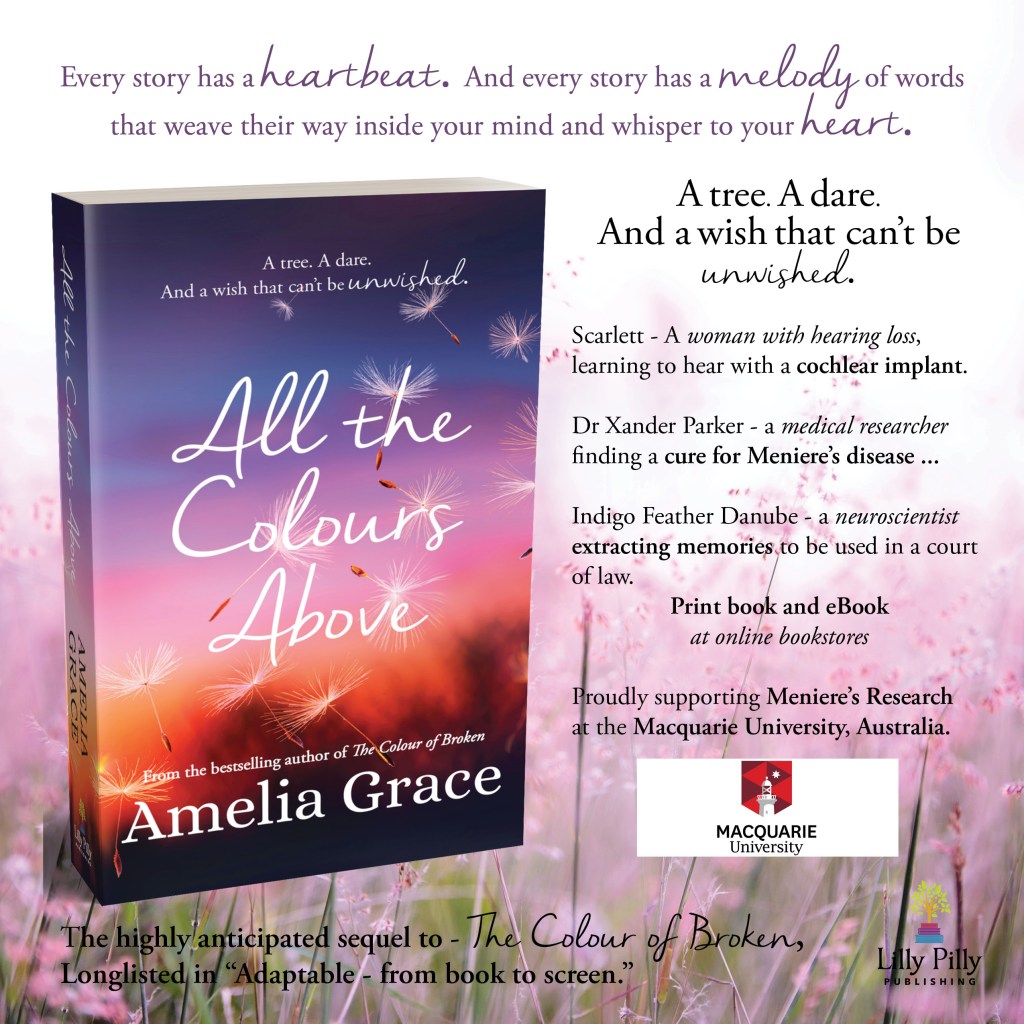

This room was named after Professor Bill Gibson who is a renowned ear, nose and throat (ENT) surgeon and world leader in cochlear implantation and Menière’s disease. My heart glowed. It was Professor Bill Gibson, whom my own ENT phoned to ask for advice before he administered my gentamicin back in 2004. It was Professor Bill Gibson, who read my Meniere’s novel, The Colour of Broken in 2018, and invited me to the Meniere’s Symposium in Sydney, 2018. It was Professor Bill Gibson, whom I emailed to apologise for curing Meniere’s in my new novel, All the Colours Above (2021), to which he replied, ‘I am interested in using nanorobotics to deliver medication to the endolymphatic sac. Mohsen Asadnia is an engineer who is very interested in Meniere’s Disease and is a leader in nanorobotics. You can google him. He is also building models to explain the cause of the vertigo.’

Two researchers spoke. My biggest apologies that I can’t acknowledge them by name, but I was in system overload with being present in a laboratory where the technology for my own Cochlear Implant was created once. The Cochlear Implant that changed my life. After looking around at the equipment, and the very place where Cochlear Implant Surgeons from all around the world come to learn how to perform Cochlear Implant Surgery, or where they watch live demonstrations on donated body parts from people who kindly give their physical body over to medical science after death, my eyes found the researchers again. More superheroes.

We saw the inner cochlear implant device that is placed under the skin on your scalp, and watched how the 22 electrodes were inserted via their ear prototype used for surgery instruction.

And then we were able to ask questions.

One of the people on our tour group asked about the part of the Cochlear Implant you wear on your head. The processor. I spoke up and showed them my Kanso 2, and how it attached to my head. I also told them about the year 2019, at Sports Day at school, when I saw a Year 7 boy who had cochlear implants on both ears. I spoke to him and was blown away by his perfect speech when answering my questions. He never once asked me to repeat what I was saying. He also happened to be Dux of Year Seven that year. He was the person who finally helped me to decide to get a Cochlear Implant. He’s in Year 10 now, and we always smile at each other and share CI information. He’s an amazing young man.

After a group photo we were lead into another room.

More Cochlear Implant research.

They are in the midst of human trials, applying hearing cell growth stimulator solution (gene therapy) into the cochlear with the electrodes at the time of the Cochlear Implant surgery. The hearing cells are stimulated to grow and attach to the electrodes to improve cochlear implant hearing even further.

You can watch a news item about the research here: https://fb.watch/dJ5Ov5gypS/

We were also shown the half a million dollar medical robot that will be used by Cochlear Implant surgeons in the near future. It’s an effective tool to overcome the surgeon’s limitations such as tremor, drift and accurate force. They joked about how good the upcoming generation of surgeons will be at controlling the joystick of the robot with all their experience in playing video games and online gaming during their youth.

We proceeded onto the next room. On shelves were rows and rows of medical equipment and three large industrial fridges. ‘Donated totally intact vestibular systems,’ I was told. ‘We don’t want to scare you with the contents.’ I wanted to tell her that’s what I planned to do with my ears – to donate them to medical research to help people with Meniere’s disease. I also wanted to tell her that I love biology and anatomy and the sciences, and seeing body parts like that wouldn’t phase me.

We moved into a long room next. If was filled with equipment for surgeons to practise Cochlear Implants. Impressive. We are in good hands.

Onward bound, we entered the Anechoic Chamber – the quietest place on earth. The purpose of this room is to test sound, and to test hearing devices. The walls and ceiling was lined with fiberglass wedges. Beneath us, we stood on mesh that covered an open two floor drop below, where again the floor was covered with fibreglass wedges. This anechoic chamber at Macquarie University is the only one in the Southern Hemisphere. Explore the anechoic chamber here: https://my.matterport.com/show/?m=wPTdUHH5PNV

I was thrilled to be inside this space. I had read about these rooms.

Inside the room it’s silent. So silent that noise is measured in negative decibels. It’s a challenge for people to be in the chamber. But your ears adapt. In the absence of external sounds, you will hear your heart beating, sometimes you can hear your lungs, even hear your stomach gurgling loudly. You become the sound. If you are in the room for 30 minutes, you have to be in a chair, as people have trouble orienting themselves and even standing. It is said that the longest anybody has been able to bear it is 45 minutes.

I wondered about us Menierians. With our loud tinnitus, many with multiple unbearably loud tinnitus sounds, would we last longer than 45minutes? Those of us Menierians who have had their balance cells destroyed, would will still be able to orient ourselves and stand due to the fact that we have relearned to walk with the absence of our vestibular balance senses? I’d be open to the challenge to be in the chamber as a person with Meniere’s disease.

Fascinating.

You can read more about anechoic chambers here: https://www.scienceabc.com/innovation/anechoic-chambers-quietest-most-silent-rooms-work-made.html

12:30 PM – 1 PM Lunch

I approached the long table of prepacked lunches as a person with Meniere’s disease. You know what we do, we look at the food and categorize whether it is safe for us to eat – how much salt content would be in the foods; would it give me brain fog, ear fullness, or increase the sound level of my tinnitus, would it be enough to throw me into a vertigo episode? I wondered what would be offered for lunch by the Meniere’s specialists, knowing our reaction and limitations with salt. I was well pleased to find that the packaged lunch was well thought-out with our diet restrictions in mind, and so very thankful for their kindness once again. But still, when I opened the box of food, I deconstructed the Turkish bread (other types of bread were available as well) to see exactly what was on the roll (chicken, lettuce, tomato) with a side salad of carrot, celery etc, plus a chocolate roll. I ate what I knew wouldn’t affect me.

1 PM- 2 PM (Discussion and planning)

With our bellies full and Meniere’s stories shared over lunch in the glorious winter sunshine (20 degrees Celsius), we headed to another room of grouped tables and chairs for discussion and planning. This is the part of the day I was unsure about. It even made me feel a little nervous. How could we, the Meniere’s sufferers, be part of planning? What could we possibly provide the highly intelligent doctors, professors and engineers, that could help them?

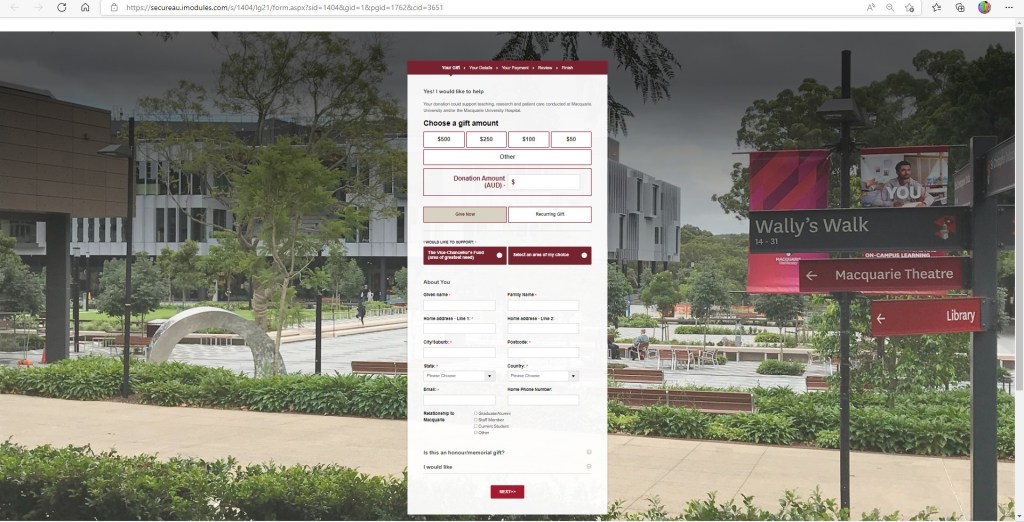

This session opened and we heard about funding for Meniere’s research. Dr Romaric Bouveret – Director of Operations and Strategies spoke, as well as another guest speaker (I apologise for not recording her name). We heard that funding for Meniere’s is hard to obtain, and they are actively applying for grants, once again. We also heard that Meniere’s comes under the umbrella of “Hearing” at the University, and so they have access to some funds through there. The sigh of relief in the room was palpable. We were also assured that any donations sent to the Macquarie University for Meniere’s (which can be chosen from the drop down menu on the donation page) would be totally committed to Meniere’s research.

The donation form: https://secureau.imodules.com/s/1404/lg21/form.aspx?sid=1404&gid=1&pgid=1762&cid=3651

And then we were given the chance to speak. At first, some of us spoke about how they may be able to find ways to donate money – this is a hard thing to do when Meniere’s has stolen your means on income.

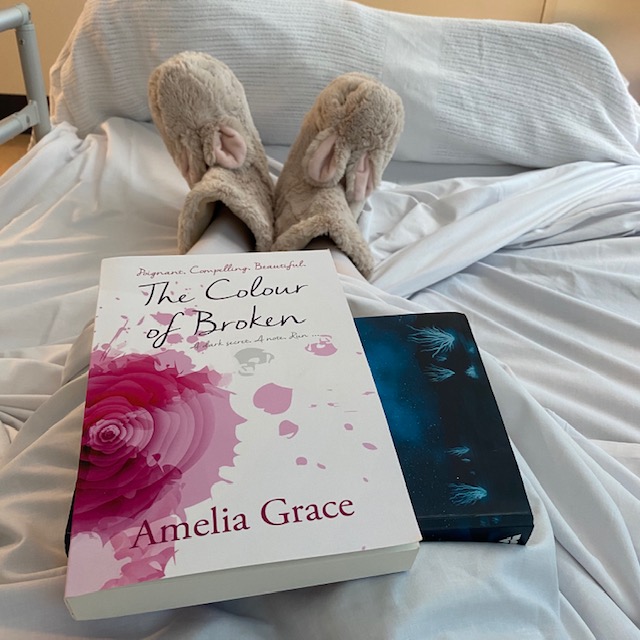

I too, joined this thread. I spoke about my two Meniere’s novels (The Colour of Broken and All the Colours Above) that I have donated a substantial amount of money to research from sales. I spoke about the impact of having a story with a main character with Meniere’s, and that a young girl in the US gave her mum a copy of The Colour of Broken … afterward, her mum came back to her begging for forgiveness, as she thought her daughter had been faking the symptoms. I also told the researchers that The Colour of Broken had been long listed, twice, to be made into a movie. Awareness for us. For Meniere’s.

Professor David McAlpine stated the importance of the Arts (writing, art, drama, music, dance, movies, film and television) for helping to raise awareness and funds. And that collaboration across fields was important. That connection to people was important, and the Arts helps us to do that.

Then with tears, I spoke about how I’ve talked Meniere’s sufferers online, out of suiciding. I don’t know if they wanted to hear that. But they needed to hear that. They need to know how Meniere’s affects the lives and hearts and souls of people. They need to know how destructive it is. We want our lives back.

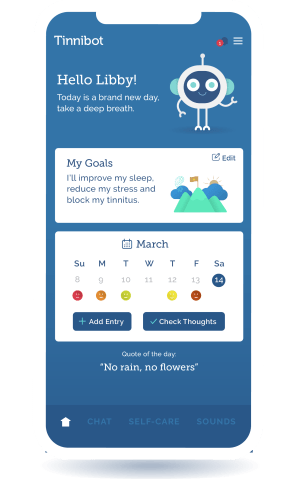

Dr Matthieu Recugnat spoke to us next. He talked about tinnitus. He talked about hearing research, and he talked about a program they have created called Tinnibot, the world’s first virtual coach (an app) that provides tinnitus support anytime, anywhere.

Professor Dave McAlpine asked, what else do we need?

I suggested they build a website that keeps people up-to-date with the latest research. I think it’s important to keep in touch with the researchers. Making connections is about hearing the stories of real people, including the Meniere’s research team stories.

2 PM -2:30 PM (Cochlear building visit)

Unfortunately we had gone overtime with the discussion and planning. And yet there was so much more to say. It was decided that the Cochlear building visit would have to be included in the next tour. I’ll definitely be attending that tour.

2:30 PM – End of the visit

I think I can speak for all of the Menierians present today – we are in awe of you, and so, so, so thankful.

My request for tours in the future:

To the Macquarie University –

• Record the tour sessions so they can be shared globally (with captions) – every word and every bit of added humour was precious.

To Anne –

• That the gathering is a day and night event, so after the tour, we can have a Meniere’s get together (and perhaps raise some money for research), and where we can share our stories, our tragedies and triumphs, and lift each other up.

As I catch my flight back to Brisbane, finally I slow down. My heart is breaking, and yet, it is full of joy. How can it be in two states at once? It’s breaking because people are still suffering terribly with Meniere’s disease. And yet it is full of joy. The future for us is looking bright. I know our cure, or resolutions of our symptoms, is coming soon.

I tuck into my ‘traditional flight home Krispy Kremes – original glazing’ and reflect on my insanely amazing day, and I hope that, while Dr David McAlpine and Dr Mohsen Asadnia are at the 2nd Inner Ear Disorders Therapeutics Summit in Boston in two weeks to share their research and findings, and to listen to other researchers on their discoveries, all the pieces of the Meniere’s jigsaw puzzle will be found.

The spark of hope can never be extinguished.

If you would like to suggest something for discussion and planning for the Meniere’s research team, please add it in the comment section, and I will pass it on to the researchers for you.

* Some names of Meniere’s people have been changed for the purpose of this blog

XX Julieann

Julieann Wallace is a multi-published author and artist. When she is not disappearing into her imaginary worlds as Julieann Wallace – children’s author, or as Amelia Grace – fiction novelist, she is working as a secondary teacher. Julieann’s 7th novel with a main character with Meniere’s disease—‘The Colour of Broken’—written under her pen name of Amelia Grace, was #1 on Amazon in its category a number of times, and was longlisted to be made into a movie or TV series by Screen Queensland, Australia. She donates profits from her books to Macquarie University, where they are researching Meniere’s disease to find a cure. Julieann is a self-confessed tea ninja and Cadbury chocoholic, has a passion for music and art, and tries not to scare her cat, Claude Monet, with her terrible cello playing.