It Will Change Your Life #4

October 31, 2019

I’m filled with so much doubt. I am choosing to get a Cochlear Implant. Am I allowed to choose? Or should I just accept my fate that I will remain without hearing for the length of my days, auditory colour disappearing from my life.

I didn’t choose to have Meniere’s disease. I didn’t choose vertigo. I didn’t choose deafness. I didn’t choose tinnitus. Just like other people who didn’t choose their incurable diseases or illnesses.

A Cochlear Implant feels like a second chance. A second chance at hearing. Of taking back something Meniere’s disease has taken from me. In my mind’s eye, I am facing the beast of Meniere’s, my sword drawn.

I want to be violent with Meniere’s. So violent. I hate it. I hate what it has done to me. What it has taken from me. I hate what it does to its victims. I want to slay it with an intensity that will obliterate it for eternity, with such force that it withdraws from bodily habitation of every person who suffers from it.

Cure come soon. Please.

I arrive in the city. I look up briefly from the footpath that I walk on. A rarity. My normal walk is focussed on the ground in front of me, ensuring each step will keep my balance. I see an old windmill on top of the terrace. Unkept grey, striking against the beautiful lilacs of the Jacaranda tree. It was built by the convicts in the late 1820s and is the oldest windmill in existence in Australia. Due to its windless location, the windmill morphed into a symbol of “dread and torture” as penal Commandant Patrick Logan used convicts to work a treadmill he had constructed to keep the arms turning in lieu of wind.

Dread and torture. Fitting. A perfect symbol for Meniere’s disease.

A weathervane decorates the uppermost part of the windmill. And there sits a crow, blacker than night. It squawks. Welcome, I hear. Today, you will learn of your fate.

I inhale deeply. My eyesight returns to the uneven, battered, cracked path in front of me. Falling is never a good thing. Once you have your balance cells destroyed, when you fall, you have no idea where to place your hands to protect yourself.

The first time I fell was Christmas 2018. We were on holiday in Tasmania, walking the Dove Lake trek at Cradle Mountain. 5.7 km. 3 hours.

After the walk we entered the cafeteria for a drink. Without warning, tears filled my eyes. In public.

My husband turned to me and the look on his face said it all. His eyes widened. ‘What’s wrong?’

‘I fell,’ I said. I wanted to sob. Loudly. Aftershock from the fall. I caught the sob in my throat. ‘I fell and I couldn’t stop it.’

His eyes filled with tears, but they didn’t leak down his cheek like mine. I always hate seeing his eyes that way. He was following me as we walked, to catch me if I fell. He always does that for me. My protector. And when it happened, there was no way he could stop it. I remember the panic in his voice as he leaned over me, asking if I was okay, looking over me, again and again. ‘Did you hurt yourself?’ he had asked.

All I could say was, ‘My phone is under the bush, over there.’ I had no idea how I saw it slide under the bush. When I fall I have no idea where to put my hands to stop me, or protect me – inside my head I see a body but no arms or legs. That’s what destroying your balance cells does. I just have to wait for impact and suffer the consequences.

‘I don’t care about your phone. Are you okay?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said. It was a lie. I was hurt. But I wanted to get up to save face. There were many people on the walking track. I HATE YOU MENIERE’S!

My husband pulled me up off the ground. My daughter picked up my phone. She was too quiet. How many times had she witnessed Meniere’s bring me to my knees with vertigo, deafness, depression? And now falling.

I blew out a long breath between my lips. Then set a rock in my sights to sit on for a moment to assess my injuries, then walked there, my husband holding onto my arm to support me. I wanted to yell at him, “LET GO OF ME. I’M NOT AN INVALID!” But I didn’t. He was trying to help.

I sat on the rock, looked over the lake and focussed on where I hurt – my wrist, my arm, my ankle and my back. Hold yourself together, I thought, people fall all the time. Put on your “I’m okay mask”.

‘Are you alright, Ma?’ my daughter asked.

Hold yourself together. The emotion of ‘I want to fall to pieces’ rolled through me. Hold it together. Breathe. ‘It could be worse,’ I said, ‘I could have broken something.’ I was hoping that I didn’t break anything. My wrist, arm and ankle were throbbing. Not to mention my back spasms. ‘Thanks for picking up my phone,’ I added.

She nodded, looking at me with concern in my eyes.

‘I’m sorry for falling,’ I say to her. I don’t want her to be embarrassed by me. I HATE YOU MENIERE’S.

And of course, she is not. She never is. She’s always one of the first to help. It is my own self-judgement that betrays me.

I stand. In pain. But I can walk to finish the last hour of the track.

My daughter is in front of me, glancing back at me once and a while, and my husband behind me. I’m glad. He can’t see me wriggling my fingers to check my wrist, and feeling where my right arm hurts, nor the wince on my face when my ankle hurts more than I want it to, or my back spasms. All I can think of is when my son would roll his ankle at elite triathlon training, and his coach would tell him to walk normally on it. So that is what I do, despite the pain.

Back at the cafeteria …

‘I could have died if I fell in a different part of the walk.’ It was true. Parts of the track were on a boardwalk above the ground that fell steeply, scattered with rocks and trees. No rails to stop a tumble.

‘I know,’ he whispered. I watch his watery eyes and see him swallow harder than usual. ‘What do you want to drink? Do you want an ice-cream?’ He was using the distraction method. He knows me well.

Claire and I find a table away from most of the people. My wrist and arm throb. My back was spasming and my ankle twinging. Swelling was setting in. I ate my ice-cream, flicking tears from my eyes when they dropped. At least I don’t have vertigo, I thought. It was a good day, after all. Any day without vertigo is a good day. Suck it up, I tell myself, it could be worse.

We enter the ENT’s reception area. I laugh then shake my head in disbelief at the choice of carpet. The pattern on it makes me nauseous – thanks to my shadow, Meniere’s.

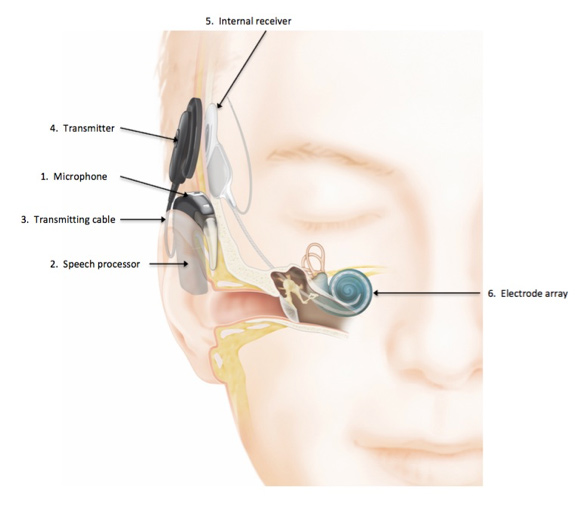

My ENT calls me in. ‘Good news,’ he says. ‘You are a candidate for a Cochlear Implant. I have signed you off on it if you wish to proceed.’

I swallow. There it is again. I get to choose.

I nod. But not with confidence. More like a ‘roll with the wave’ type of nod. I’m following a path but not certain of that is where I am meant to be. How will it change my life?

He refers me to a surgeon, and then as I leave, I thank him for his support throughout my Meniere’s journey.

‘You don’t know how difficult it has been for me, when there was nothing I could do to help you,’ he says.

‘But I am one of your success stories,’ I remind him. I wouldn’t be standing here today if it wasn’t for his help.

He shakes my hand. ‘Keep in touch. I want to know how you go.’ He gives me a smile.

I walk out of his office and numbness sets in. I’m a cochlear implant candidate. This just became real.

Next step. The Cochlear Implant Surgeon appointment.