It Will Change Your Life #9

Wednesday, 27th November – balance therapy

Balance

/ˈbal(ə)ns/

noun: balance; plural noun: balances

1. an even distribution of weight enabling someone or something to remain upright and steady.

In 2004 I made a conscious decision to have my balance cells destroyed. I couldn’t do the horrendous, unpredictable, debilitating, violent, torturous, four-five hours of insane vertiginous spinning and nausea and vomiting and staring at one focus spot for the entire four-five hours anymore. I was more than done. So when my ENT offered to inject gentamicin into my middle ear to kill off the balance cells, halting the vertigo, I didn’t think twice.

Was the gentamicin my first port of call? Absolutely not. I had already had Meniere’s disease for 9 years and tried:

* Low salt diet

* Diet elimination

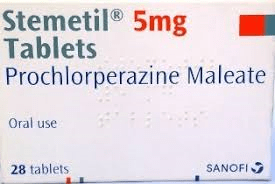

* Stemetil

* Diuretic

* Serc

* Sound therapy

* Acupuncture

* Prednisone

* Grommet

* Gentamicin. The gentamicin worked. One shot injected in through my grommet with some bicarbonate of soda and sterile water mixed with it to make it penetrate better.

The procedure took place at my ENT’s procedure room in the city. I lied on my right side while he injected the concoction in through my grommet.

‘Isn’t that hurting?’ he had asked me as he infused the mixture into my middle ear.

‘Yes,’ I had said, ‘but I am envisaging it destroying the Meniere’s in my middle ear. It’s a mind visualisation technique I taught myself when I was young, when I had growing pains.’

I remained on my right side, left ear facing the ceiling for 20 minutes after the procedure, then went home, where I went to bed and rolled onto my right side to keep my left ear up. I slept for 2 hours.

The next day I had bouncy vision when I walked. It has a term – oscillopsia. And was a side effect of having my balance cells destroyed. It was a good sign that the gentamicin was working, my ENT had said.

https://www.healthline.com/health/oscillopsia

Three weeks later I was back teaching full-time, learning to trust that I wouldn’t have anymore vertigo attacks. Fifteen years later, I am still vertigo free.

Choosing to destroy my balance cells to stop the vertigo was not a hard decision. Meniere’s disease had total control on my life, and I wanted it back. There was a risk of losing all of my hearing, but that was a preferred choice to suffering through the torturous vertigo anymore. The gentamicin stopped the vertigo.

I gained quality of life again – socialising, working, independence, driving, and slowly became more confident in my life.

I lost a little of my hearing, but not a lot.

If my vertigo returned, would I do it again?

Yes.

When I joined global Meniere’s groups, I discovered that others who had had this procedure done, were having balance therapy. I was shocked that there was even a thing called balance therapy. When I had my procedure done in 2004, balance therapy didn’t exist where I lived. I had to learn to walk again, finding my new balance, learning my limitations as I went. No help.

Today, I sit in the reception of the Vestibular Therapist’s office, with a referral from my Cochlear Implant surgeon.

Mandy greets me with a smile. The universal language that puts you at ease. Curiosity, and my shadow, Meniere’s, follow her to her office. I sit on a chair and she questions me about my Meniere’s history, writing notes.

‘I’m an concerned about your imbalance after 15 years. You should not have that deficit anymore. It may point to another problem you have. Do you have Meniere’s in your right ear,’ she asks.

‘No,’ I say. Anxiety joins us in the room.

She frowns at me. ‘Let’s do some tests and see what is going on.’

She asks me to balance with my eyes closed for 30 seconds. I pass this test. 😊

She asks me to walk across the room, heel to toe, heel to toe, heel to toe. I fail miserably. Two steps and I fall over. ☹

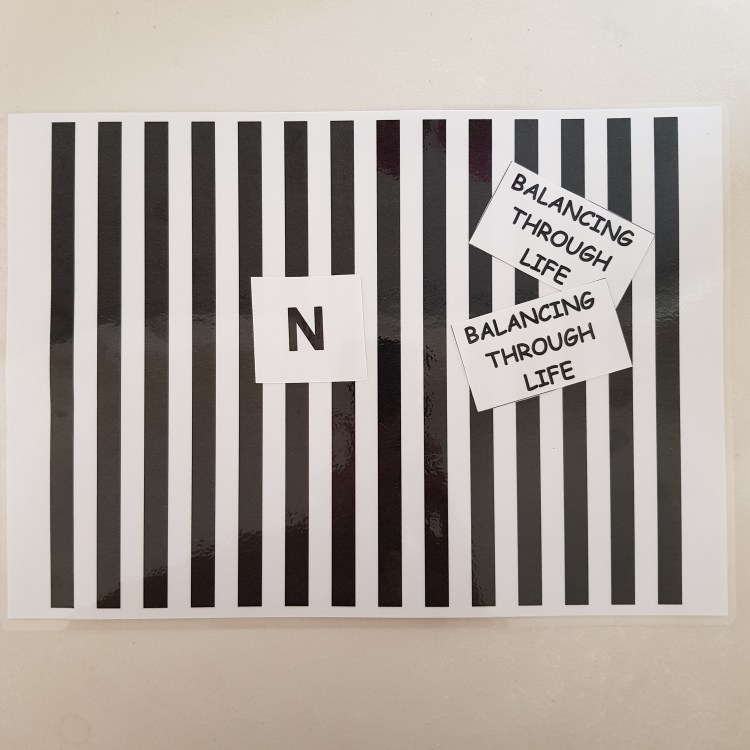

Then she asks me to look at the letter “N” on the wall, and moves my head left to right over and over and over, quickly, then asks me whether the letter moves. Yes. She repeats that test, but moves my head up and down over and over and over, quickly, asking whether the letter “N” moves. Yes.

Mandy sits close to me on my left. I have to sit at a 45-degree angle to her and focus on her nose. She then moves my head left to right over and over and over again, quickly. ‘That’s not too bad,’ she says.

She repeats the test, but this time she sits on my right side. I try to keep my focus on her nose as she moves my head left to right over and over and over again, quickly. I can not keep my focus on her nose at all. ‘Yes. That’s the gentamicin damage in your left ear,’ she says.

I sit on a massage table.

Mandy places some goggles over my eyes. She wants to see if I have Benign paroxysmal positional vertigo (BPPV). She does the Epley manoeuvre. No vertigo or eye movement evident.

Mandy stands and talks me through some vestibular exercises for neuro-plasticity – the brain relearning balance. I cannot express how happy I am to get these exercises. They will help me no end.

Except, each of the exercises make me feel insanely nauseous. I blow a controlled breath through my lips. I’m an expert at it.

‘Do you want to stop?’ she asks me during each exercise.

‘No,’ I say. ‘I can do this.’ And I get through to the end.

‘Can I take stemetil when I feel nauseous with the exercises?’ I ask.

‘No,’ she says. ‘It’s a vestibular suppressant, and your brain won’t learn the new balance pathways and desensitisation.’

‘What about Serc?’ I ask.

‘No. Don’t take Serc either,’ she says.

‘But it is only supposed to increase the blood floor in the inner ear,’ I say.

She shook her head. ‘No. That’s what they want you to believe. It a vestibular suppressant, like stemetil – it’s good for Meniere’s, but not other vestibular conditions.’

‘Some doctors say it does nothing for Meniere’s,’ I say, frowning, recalling how my own ENT and the Cochlear Implant ENT scoffed when I mentioned Serc. I wondered why the makers of Serc would say it increases blood flow, while the vestibular therapist, who specialises in vestibular retraining says it’s a suppressant. I know for a fact that many Meniere’s people say Serc keeps their vertigo at bay.

‘From the conferences I have attended, it does indeed work for many Meniere’s patients, not all though,’ she adds. Yeah, I was one who it didn’t work for, I think.

I leave her vestibular therapy room, which is in a really old house that is not level. I catch my balance as I walk through it. My shadow, Meniere’s, laughs at me. I am armed with vestibular exercises, and an appointment for next week.

I have now completed all of my necessary Cochlear Implant work-up appointments.

Next stop, the Cochlear Implant. December 19th.